WHAT DO turtle habitats, quail farming, artificial reefs, and a four-wheel drive have in common?

They are all part of Malaysia’s conservation initiatives run by state-level authorities and funded by the federal government.

Nearly every year since 2019, Malaysia’s federal government has been transferring money to state governments under a mechanism known as the Ecological Fiscal Transfer (EFT). The funds serve to incentivise state governments to improve biodiversity conservation and establish new protected areas.

Between 2019—2024, Putrajaya disbursed RM517 million in EFT funds. By 2025, the total allocation has reached RM800 million. The funds had financed at least 270 projects to completion by 2022, said Dr Khairul Naim Adham, the head of strategic planning in the biodiversity management unit at the Ministry of Natural Resources and Environmental Sustainability (NRES).

The federal government should give more, say conservationists. Putrajaya allocated RM250 million for EFTs in Budget 2025 – up from RM60 million in Budget 2019. Conservationists are calling for EFT funds of up to RM1 billion annually.

But how effective is the EFT scheme? The federal and state governments have had 6 years to deploy the funds. How have they used it, and what have they achieved?

How are EFT funds allocated?

The EFT scheme was first implemented in Malaysia in 2019. When then-finance minister Lim Guan Eng presented the national Budget 2019, he said the federal government would allocate RM60 million to state governments for “efforts to protect and expand existing natural forest reserves and protected areas.” The amount increased to RM70 million in 2021. (There was no allocation in 2020.)

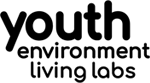

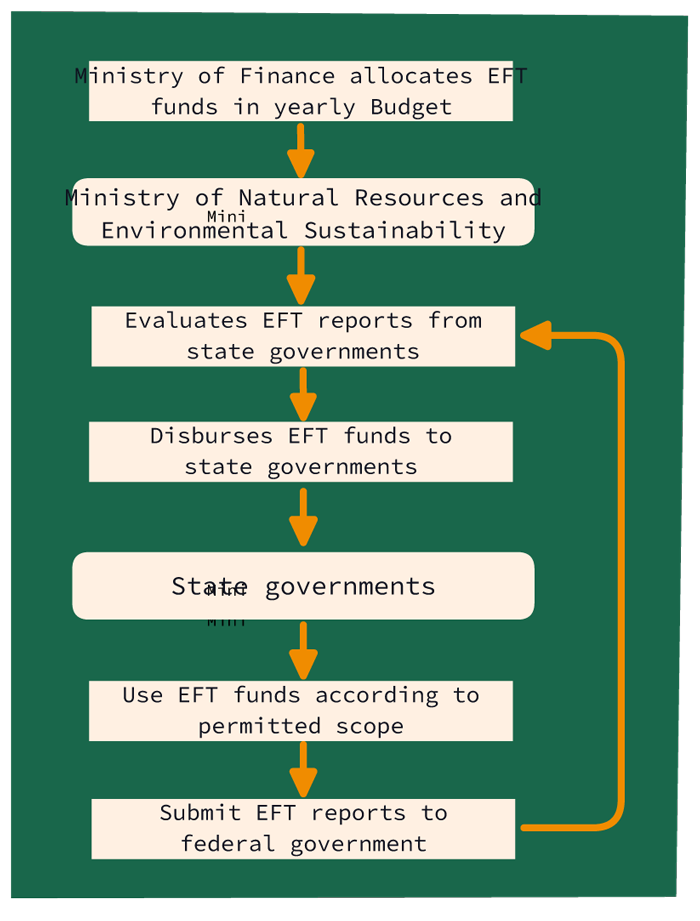

Every year since 2019, except for 2020, the federal government has been disbursing EFT funds to state governments. The state governments decide how to spend the funds according to the permitted scope and send yearly reports on project outcomes to Putrajaya, NRES told Macaranga. NRES then evaluates the reports to allocate future EFT funds.

Ecological fiscal transfer flowchart

Malaysia has committed to conserving at least 30% of its land and seas. The target is set in the National Biodiversity Policy 2016-2025 and the newer National Biodiversity Policy 2022-2030.

But these are federal government targets for matters beyond their powers. The country’s Federal Constitution gives state governments final authority over land and coasts.

Therefore, environmental groups such as WWF-Malaysia have advocated for financial transfers from the federal government to state governments to better care for their natural ecosystems and partially cover the costs of doing so.

“It’s something that WWF-Malaysia has been advocating for about 5 to 10 years prior to it being [introduced] in 2019,” said Lakshmi Lavanya Rama Iyer, the organisation’s policy and climate change director.

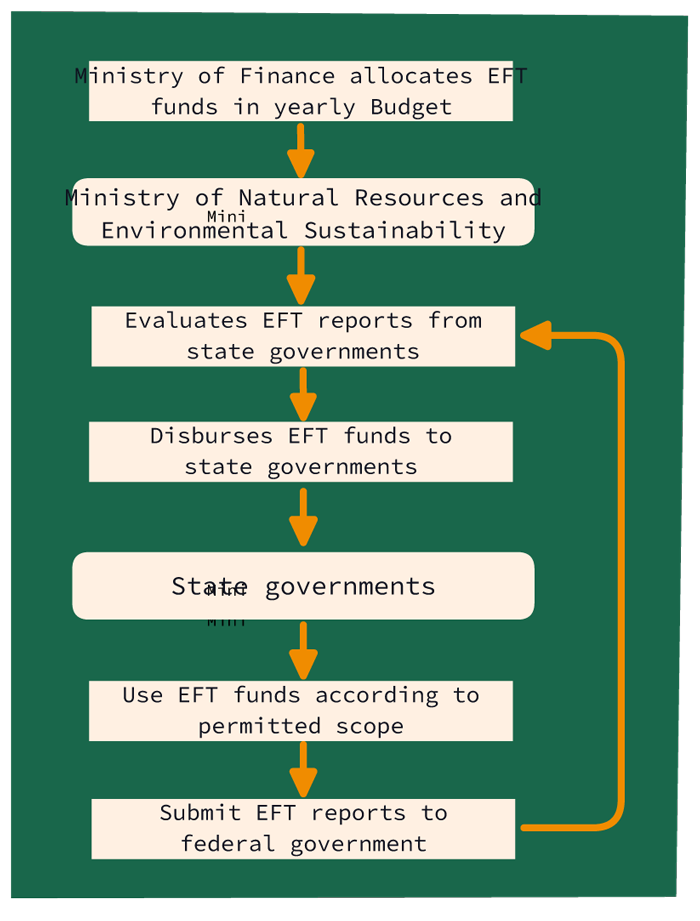

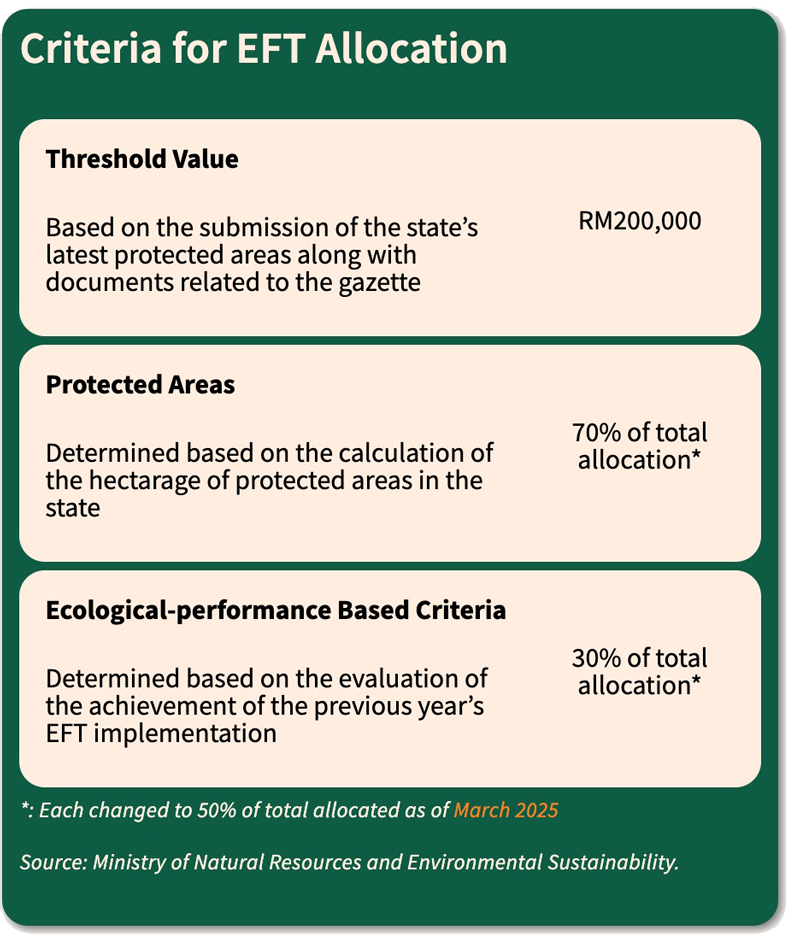

Neither Budget 2019 nor Budget 2021 specified criteria for allocating or distributing the funds. RESCU, a natural resource management consultancy commented that “initially, the funds were distributed to states without much control.”

A set of criteria for EFT allocation and scope for usage was finally issued in January 2022 by the then-Ministry of Energy and Natural Resources.

Outcomes of EFTs

Since 2019, the federal government has disbursed RM517 million in EFT funds to state governments. The state governments then decide how to use these funds according to scopes set by Putrajaya.

What have state governments achieved so far?

Expansion of protected areas

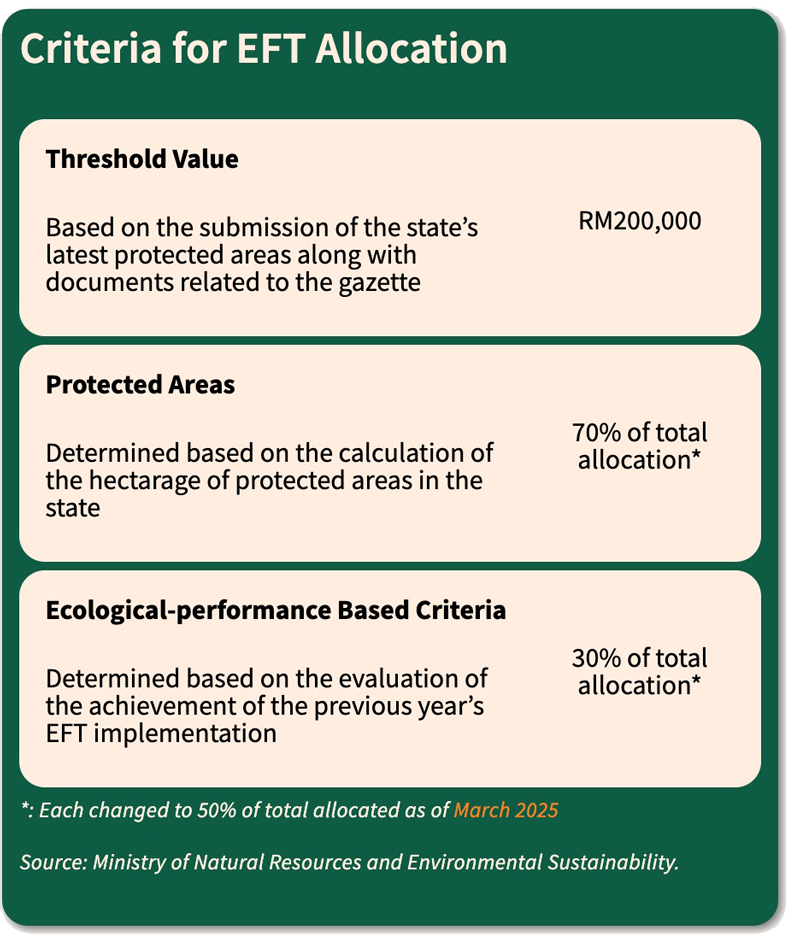

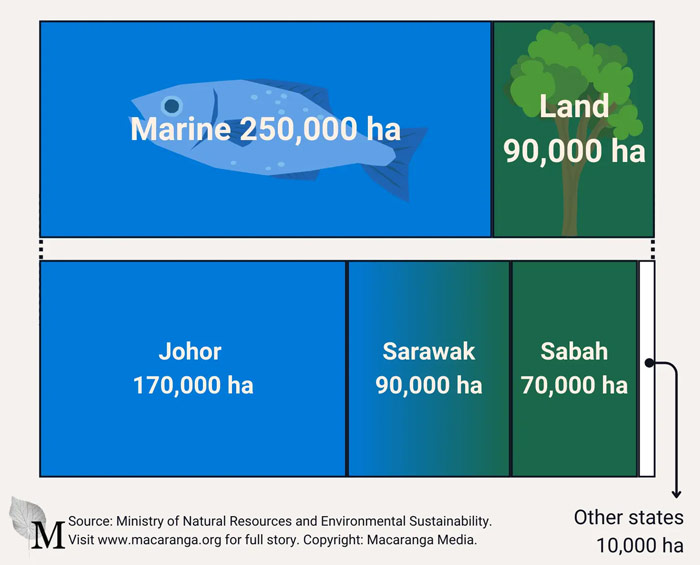

EFT funds had driven “impactful conservation projects” in 2021—2023 that added about 250,000 ha and 90,000 ha of protected areas on land and sea, respectively, said NRES. Almost all the gains came from three states: Johor, Sarawak, and Sabah.

(Note: While the figures for new protected areas above sum up to 340,000 ha, NRES had at times used “350,000 ha” instead.)

Protected areas added under EFT (2021-2023)

The EFT funds also supported the Department of Wildlife and National Parks of Peninsular Malaysia (PERHILITAN) ‘s Biodiversity Protection and Patrolling Programme, said NRES. This programme started in 2020 and recruits Orang Asli and army veterans to combat poaching and logging in protected areas.

However, the exact outcomes of EFT remain unclear without more granular information. We had asked NRES for these, but they did not provide them. They did not list a breakdown of EFT funds distribution by scope or even exemplary state projects.

We searched the internet for EFT-funded projects and found some scattered reports. For example, in Kelantan, EFT funds contributed to a RM2.2 million programme to build and deploy 70 cuboid artificial reefs in 2024. Artificial reefs are used to facilitate coral reef growth and boost marine biodiversity.

Four states to focus on

Without further guidance from NRES, we narrowed our reporting to the states that had received the most EFT funds.

In 2019—2024, Sabah, Sarawak, and Pahang were the top recipients of EFT funds. NRES Minister Nik Nazmi Nik Ahmad revealed the distribution data in response to a question raised by Kluang member of Parliament Wong Shu Qi in parliament, December 2024.

The data also showed a notable change in Johor’s EFT funds. Allocations for Johor have always been one of the smallest among the states, but spiked nearly 4-fold in 2024 compared to 2023.

Meanwhile, in Peninsular Malaysia, Pahang has received the most cumulative funding since EFTs were first introduced.

Macaranga sought to understand how these 4 states – Johor, Sabah, Sarawak, and Pahang – have put their EFT funds to work. Johor – an EFT outperformer Johor received RM24.7 million in EFT funds in 2024, a huge increase from its 2023 sum of RM6.7 million. What did Johor do right?

First, Johor received the RM200,000 given to any state that updates information on their protected areas.

Another RM16 million was allocated based on “the evaluation of reports from the state” under NRES’ ecological performance-based criteria. The ministry did not say what the reports contained.

Finally, Johor also received RM8.7 million in 2024 for increasing its marine protected areas and reporting them through the Department of Fisheries Malaysia, said NRES.

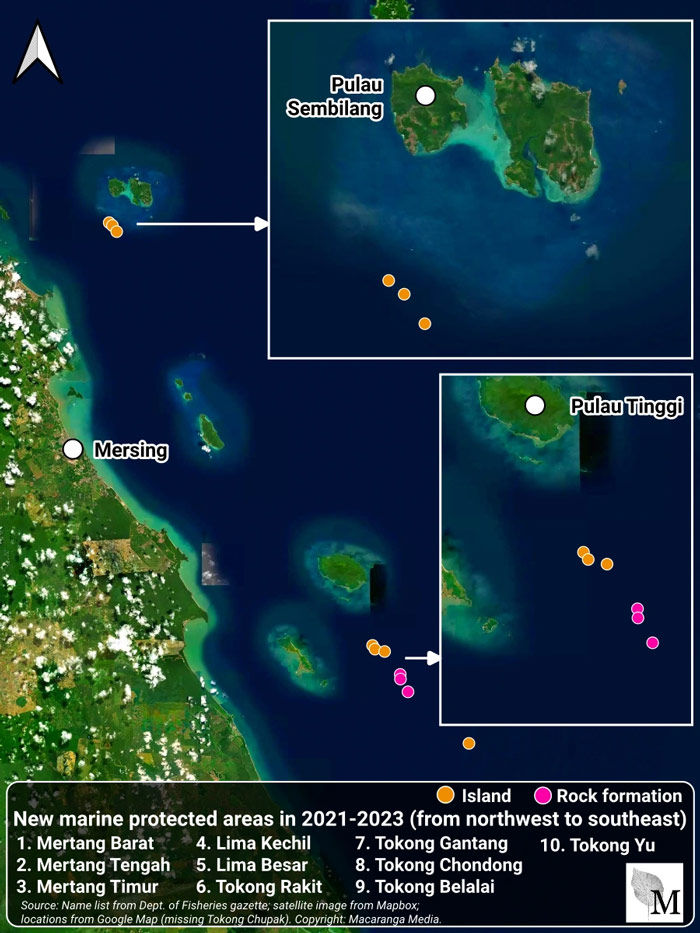

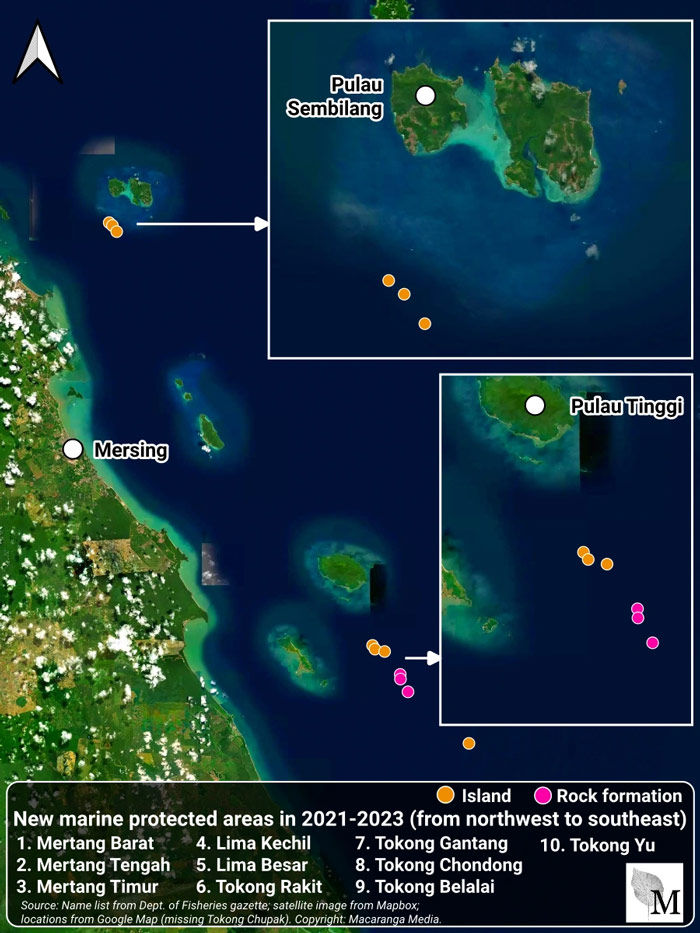

Johor’s State Economic Planning Division (BPEN) told Macaranga that using the EFT allocation, the state government gazetted 7 new islands and 4 rock formations off the coast of Mersing as part of the Sultan Iskandar Marine Park in 2021.

“All these marine areas have been gazetted under Section 41 of the Fisheries Act 1985,” Johor’s BPEN told Macaranga.

That gazette, Macaranga found, is dated 17 November and issued by the federal government. Under the Fisheries Act, only the federal Minister has authority to gazette marine park areas.

Johor’s new marine protected areas

The new marine park areas protect critically endangered hawksbill turtles, green turtles, dolphins, porpoises, and seagrass meadows for key dugong populations, according to the park’s website. The islands also harbour 114 coral species and 173 coral reef fish species, according to a 2024 report by WWF-Malaysia.

Johor’s BPEN said that under the scope of activities approved by NRES for the use of the 2021 to 2023 EFT funds, it had provided materials for programmes to restore marine life as well as conducted conservation, restoration, and enrichment works for riverine sources of fish, shellfish, turtles and endangered species.

The agency did not disclose how much it spent on each of these activities.

Sabah – supporting communities and research

Meanwhile, Sabah, which is the top recipient of EFT funds, has added about 70,000 ha of new protected areas on land in 2021—2023. However, it is unclear exactly where these are.

According to the Sabah Forestry Department’s annual reports, the state introduced 2 new protected areas in 2023. It also reclassified 51,265 ha across 9 locations as Totally Protected Areas (TPA) in the same year.

The Sabah Forest Enactment 1968 stipulates that changes to forest reserve classification must be published in a government gazette to be legally effective. But in 2021—2024, Sabah published only 4 gazettes under the Forest Enactment, none of which were on the changes to forest reserves.

We also could not determine how Sabah used their EFT funds to increase or maintain the nearly 70,000 ha of new protected areas.

One would assume that much of the funds were channeled to the Sabah Forestry Department, as the new protected areas were entirely on land.

But the Sabah Forestry Department told Macaranga that it first received EFT funds only in October 2024. That tranche was RM6.8 million – just 19% of Sabah’s RM36 million EFT allocation that year.

The Sabah Forestry Department said it spent the 2024 EFT funds for community development in villages bordering TPA forest reserves. These were Kampung Ranggal and Kampung Rosob Contoh in the Pitas district and Kampung Dumbun and Kampung Pulutan in the Sook district.

The funds helped villagers to develop animal feed processing, quail farming, and hydroponic vegetable cultivation. The efforts sought to improve the villagers’ livelihood and reduce their need to exploit the forests, said Frederick Kugan, Sabah’s chief conservator of forests. The projects also build stronger ties between foresters and villagers, which help to protect the forest reserves.

The Sabah Forestry Department has also used EFT funds to update spatial data at a protected forest reserve and establish a permanent sample plot there.

Sarawak and Pahang – lacking data

While the government agencies in Johor and Sabah explained how they used their EFT funds – albeit only partially – the same cannot be said of Sarawak and Pahang.

Sarawak has received RM63 million in EFT funds since 2019. But we did not find any records of how the funds have been spent. Neither the Sarawak Ministry of Urban Development and Natural Resources nor NRES replied to questions on the matter.

However, Macaranga learned from news reports and state government data that Sarawak has been increasing the size of its protected areas. Since 2021, the state has expanded the Batang Ai National Park and the Fairy Cave Nature Reserve, and established the Burung Sarang National Park and the Bajoh-Ujong Murod Protected Forest. These added 20,230 ha of new protected areas.

The state proposes to gazette an additional 814,437 ha as permanent forest estates. However, permanent forest estates can be logged and are not necessarily protected areas.

As for Pahang, which received RM56.5 million by 2024, the state’s financial office did not respond to our enquiry on how it used the EFT funds.

In a press release in 2022, NRES announced that Pahang had spent RM4 million to improve the management of Tasik Chini, Malaysia’s first UNESCO Biosphere Reserve. But, the Pahang Forestry Department did not respond to our requests for more information.

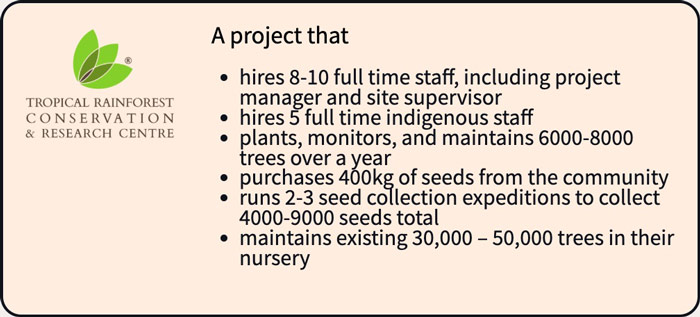

Activities environmental groups say they could do with RM1 million a year

Data gaps and confusion

We had set out to check the effectiveness of EFT funds in conserving nature in Malaysia. Official data painted bright spots, especially the addition of 340,000 ha of protected areas. However, verifying the official narrative or tracking the outcomes of EFT-funded projects has been difficult. For example, the legal documents necessary to confirm the new protected areas in Sabah and Sarawak were not found.

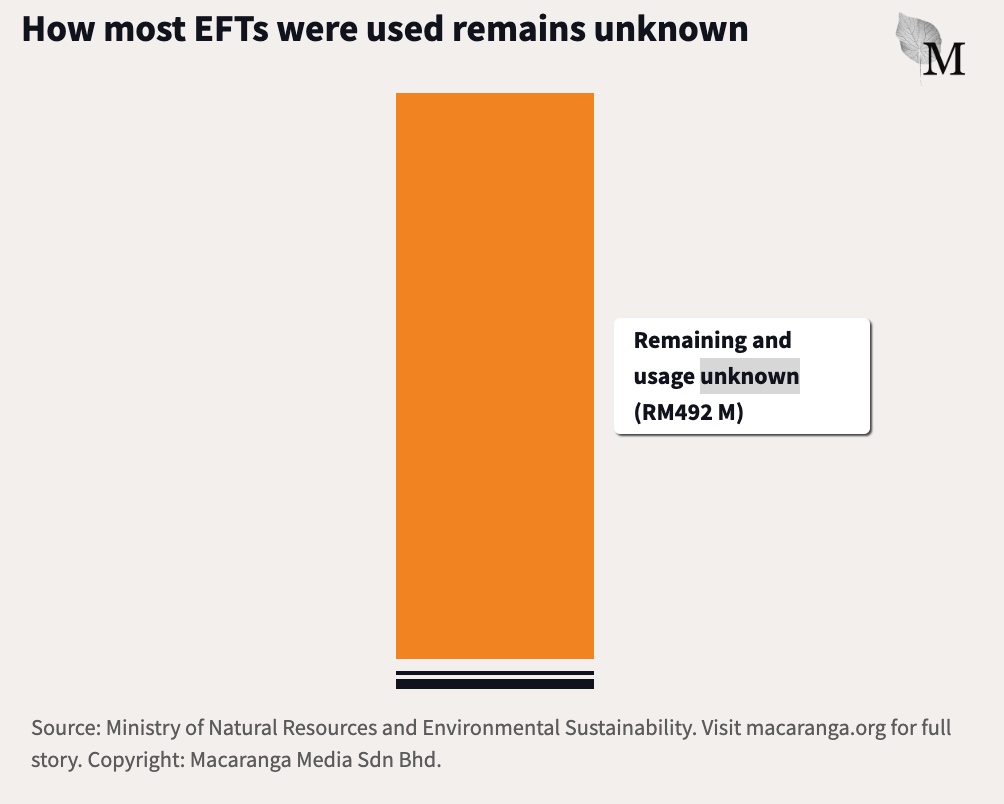

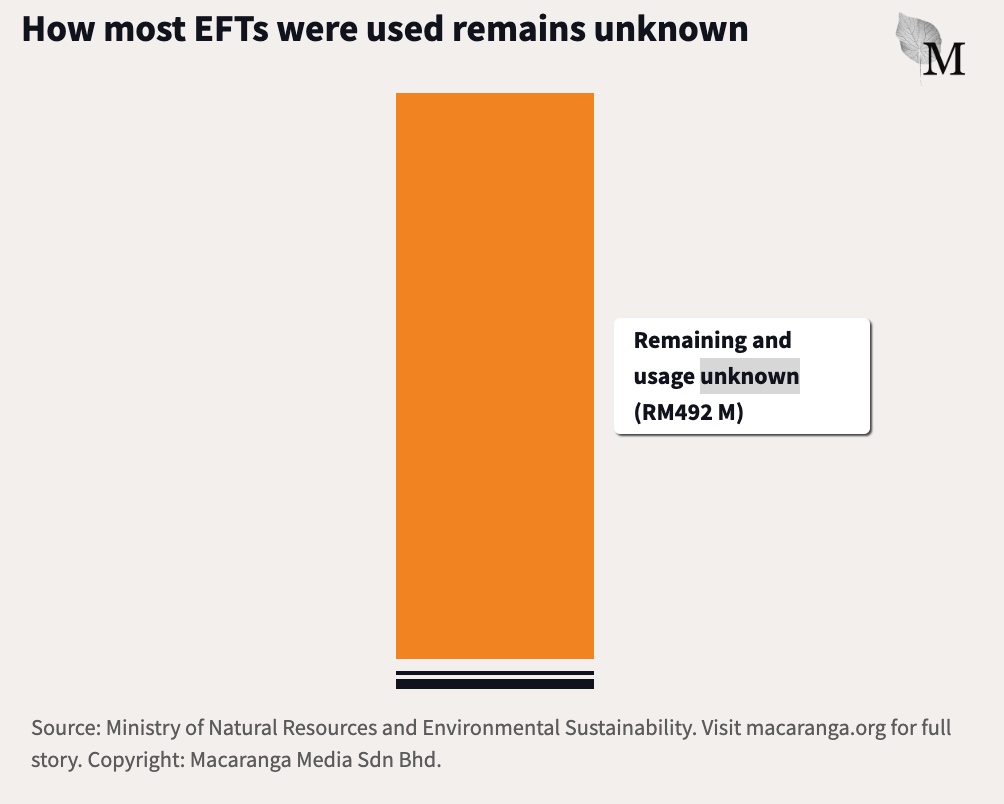

We could only demonstrate how state governments used RM25 million, or just 4.8%, of the total RM517 million disbursed in 2019—2024.

Without further information from NRES and state government authorities, Macaranga could not determine the extent of the EFT’s effectiveness beyond increasing the size of protected areas in several states. None of the 10 environmental consultants and conservationists we spoke to have an answer.

Even state governments themselves have been confused over the allocations. A June 2024 report by the Institute of Strategic and International Studies Malaysia, a think tank, stated that “a pervasive lack of clarity on the eligibility, selection criteria, disbursement procedures and intended usage of the funds persists in most states.”

“Perak, for example, allegedly did not receive any funds at the time of writing. Conversely, Sabah reportedly found RM20 million in its coffers without prior notification, creating confusion about the purpose of these funds,” the report stated.

More transparency and accountability, please

When asked if the increasing EFT allocations by the federal government have significantly motivated state governments to conserve nature, environmental lawyer Preetha Sankar said that accurate data is needed to demonstrate that has been the case.

Preetha was a legal consultant with the United Nations Development Programme in 2018 when the EFTs were drafted for inclusion in the 12th Malaysia Plan.

“The addition of protected areas would indicate that the incentive has led to a quantitative trajectory, but as for natural resource management effectiveness, I’m not certain if the information is accessible,” she told Macaranga.

Preetha also pointed out that it is unclear if EFT funds have persuaded state governments to conserve nature instead of exploiting their natural resources.

“I think the jury is still out on that. We need honest discourse on the matter,” said Preetha.

RESCU’s report said that the EFT’s annual reporting requirements currently allow the federal government to maintain a national-level database of protected areas. “Such a database would provide an unprecedented opportunity to monitor the states’ progress towards the 20% protection target,” it said, referencing the proposed 20% of terrestrial areas and inland waters to be conserved under the National Biodiversity Plan.

Making this data available would “increase the accountability of decision-makers and allow civil society to assist in monitoring encroachment and verifying reporting.”

Preetha shared a similar view. “If we are committed to good governance, then surely more transparency in EFT at all levels would be ideal,” she said. This ranges from the Ministry of Finance explaining what factors or formulas it uses to decide on the total EFT allocation each year, to getting information at the sub-national level about what agencies and projects have received EFT funds.

“The list of projects fully or partly funded by EFT would be beneficial,” she said.

Source: https://www.macaranga.org/tracking-the-outcomes-of-malaysia-ecological-fiscal-transfers-eft-for-nature-conservation/