Note: This story might contain factual or contextual inaccuracies as it was submitted by the authors as part of a competition and was published for the judges to evaluate without any editing or corrections made by the organisers or YELL.

When Malaysia’s first Apple Store opened in TRX, people lined up at dawn. Some waited for hours, all for the new iPhone 16. It’s not a new sight. Digital gadgets launches have drawn crowds for years. But in today’s digital age, the urge to upgrade feels more common. This craving for the latest tech is growing. Chasing upgrades even when our phones still work fine. Why? Upgrading usually happens even when the phone still works fine. Maybe it’s about style, social pressure, or simply a habit. This constant cycle of buying and discarding feeds a hidden crisis. E-waste is piling up. Fast. And we rarely stop to think, at what cost does “new” really come?

People buying the newly launched phones at Sunway Pyramid, 2025 (Credit: Zhang Tong)

For most Malaysians, old phones don’t go far. They end up forgotten in drawers or passed to someone else. Nia, a law student, admits, “I don’t really get rid of it, I just keep it because I have some personal stuff in it”. She’s gone through around ten phones, nearly all iPhones. Ajay, an ADP student, prefers to make his phone last as long as possible. “I will only get a phone when it completely stops working or fully breaks down,” he said. While some have heard of recycling or repair shops, few have used them. Most say they’d be willing to keep their phones longer to protect the environment. But in practice, that’s easier said than done.

Discarded, Dismantled, or Reborn?

When a smartphone is passed along, sold, traded in, or simply given away, its journey becomes unpredictable. Some are lucky. Gabriella, a PR student, sold hers through a trusted friend: “I usually just go to him when I need to sell.” Devices like hers often end up in secondhand hubs like Plaze Low Yat or SS15, where they’re wiped clean, refurbished, and given a second life – often in East Malaysia or neighboring countries, where demand for affordable models remains strong.

But not all phones meet that fate. According to Nadzirah Rosley of 1Utama Recycling Center, many discarded phones are still functional but get passed on simply because of forgotten passwords or cosmetic damage. “Some are discarded just because the owners forgot their passwords or don’t know how to reset them. A lot of our customers are quite wealthy, so they don’t bother trying to recover or repair the device,” she notes, “They just want to get rid of it quickly.”

Nadzirah Rosley at 1Utama Recycling Center. (Credit: Zhang Tong & Puteri Nor Alisha)

Nadzirah Rosley at 1Utama Recycling Center. (Credit: Zhang Tong & Puteri Nor Alisha)

Phones deemed unfit for resale may enter informal channels, where unlicensed operators dismantle them with acid or fire to extract precious metals, leaving behind invisible toxins. Then there’s the gray area of repair shops, where low-cost fixes come with unknown risks. As one technician admits, some repairs help, others just make the danger worse.

Every phone leaves its user eventually, but the system doesn’t leave the phone. What happens next depends less on the device itself than on whose hands it lands in.

The Toxic Cost: E-Waste in Malaysia

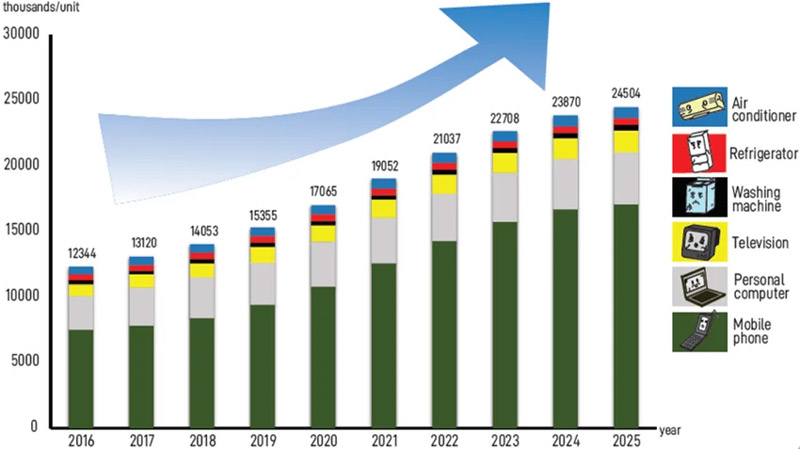

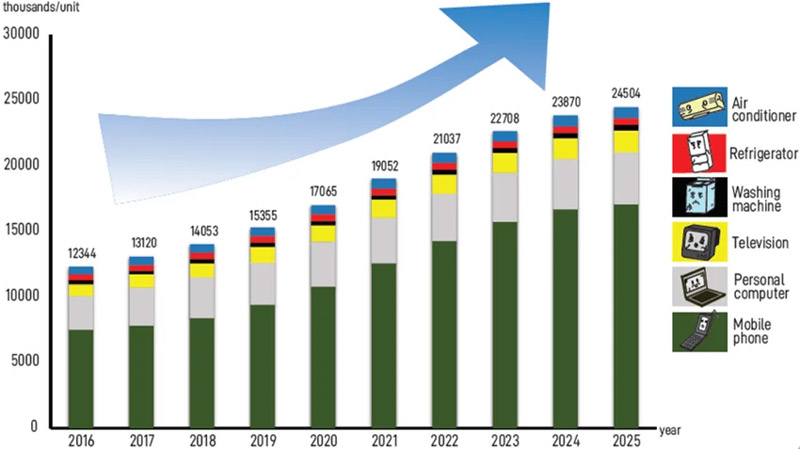

E-waste – discarded electronics like phones, batteries, and laptops – is one of the fastest-growing waste streams worldwide. Malaysia is no exception. By 2025, the Department of Environment estimated over 2.45 million metric tons of e-waste from households and businesses, with phones and their batteries being a major contributor.

Projection of E-waste Generation in Malaysia. (Credit: Department of Environment, 2022)

Projection of E-waste Generation in Malaysia. (Credit: Department of Environment, 2022)

But not all e-waste gets treated equally. Much of it ends up in informal recycling chains, where devices are dismantled without safety measures. According to researcher Afroz and others’ findings, improper disposal, like open-air burning or dumping, releases toxic heavy metals (lead, mercury, cadmium) that seep into soil and water. Workers in these operations face skin damage and toxic exposure, often without basic protective gear.

This gap between awareness and action fuels a silent crisis — one where dead batteries and broken screens pile up, poisoning the land bit by bit. But as awareness grows and better systems emerge, a key question remains: can we, as consumers, break the habit and choose a more sustainable way forward?

The Way Forward: Can We Break the Habit?

Breaking Malaysia’s toxic upgrade cycle won’t happen overnight — but change is possible. Experts and NGOs urge users to pause before upgrading, especially when phones are still functional. Instead of discarding, consumers can repair, donate, or recycle through certified collectors like ERTH, Recircle, PJ Eco Recycling Plaza, or campaigns led by Zero Waste Malaysia.

Front desk of PJ Eco Recycling Plaza, where various electronic devices were collected and recycled. (Credit: Zhang Tong & Puteri Nor Alisha)

Front desk of PJ Eco Recycling Plaza, where various electronic devices were collected and recycled. (Credit: Zhang Tong & Puteri Nor Alisha)

Initiatives like PEKA’s community “e-waste drop zones” and mobile apps that locate Department of Environment (DOE) – approved sites make responsible disposal more accessible. But challenges remain: economic incentives often pull users toward informal recyclers, and many are unaware of the environmental stakes.

Still, bridging the gap between awareness and everyday habits remains a work in progress – and it starts with changing how we value the devices we already own. Learning to extend a device’s life – through basic screen repairs or battery swaps, often taught via YouTube, can also reduce waste. “It’s not just about saving money,” Nadzirah said. “It’s about protecting what’s left of our environment.”

Upgrade the Way We Think

The next time a new phone launch lights up your screen, pause. Ask yourself: do I really need it, or do I just want it? In a world where tech moves fast and desire moves faster, it’s easy to fall into the upgrade trap. But every phone we discard too soon carries an unseen cost: to the air we breathe, the rivers we drink from, and the people who dismantle our old devices without protection.

Change doesn’t mean never upgrading; it means upgrading our mindset. If we can stretch the life of one phone, choose a certified recycler over convenience, or ask where our old devices go, we begin to shift the system. Because in the end, sustainability isn’t about perfection. It’s about intention and whether we choose to see “old” not as obsolete, but as still worth something.

Disclosure: The authors used AI tools (Grammarly and ChatGPT) to assist with spell-checking and language refinement. The authors reviewed and finalized all content.

This story is a finalist entry that was produced as part of the “Environmental Stories Workshop and Competition”. The workshop and competition was co-organised by Macaranga Media, Universiti Malaya, and Taylor’s University. The event was funded by a grant from Youth Environment Living Labs (YELL), administered by Justice for Wildlife Malaysia. The content of this story does not necessarily reflect the opinion of YELL and their partners. The Award Ceremony will be held on 2 August at Universiti Malaya.

References List

Afroz, R., Masud, M. M., Akhtar, R., & Duasa, J. B. (2013). Survey and analysis of public knowledge, awareness and willingness to pay in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia – a case study on household WEEE management. Journal of Cleaner Production, 52, 185–193.

Ismail, M. A., Lamsali, H., & Lee, C. T. (2019). Trends and issues of electronic waste and mobile phone waste: A review of Malaysia context. Jurnal Pembangunan Sosial, 37-47.

Balde, K., Wang, F., Huisman, J., & Kuehr, R. (2015). The global e-waste monitor 2014. Bonn,

Sources:

https://www.macaranga.org/team4-ewaste/